On the Move

By Allison Salerno

At 22, Clayton Carte already is making a name for himself in local politics.

Share the Story on FacebookShare the Story on TwitterShare the Story via EmailShare the Story on LinkedIn

Winter 2020 | By Kelly Petty

On a sweltering evening in Moultrie, Georgia, a group of more than 100 students, professors and volunteers unloads packs of healthcare supplies and sets up makeshift triage units at a migrant camp on one of the many farms in the small town.

While the group fights off mosquitoes and gnats, several men come out of their homes in the camp and line up to receive health checkups. The wives chat with each other and watch all of the activity happening while the children play and peek out windows.

The migrant camp is small and outfitted with the bare necessities: bathrooms, a mess hall for eating and a row of housing units for the farmworkers and their families. As dusk settles into night, the camp swells with hundreds of patients.

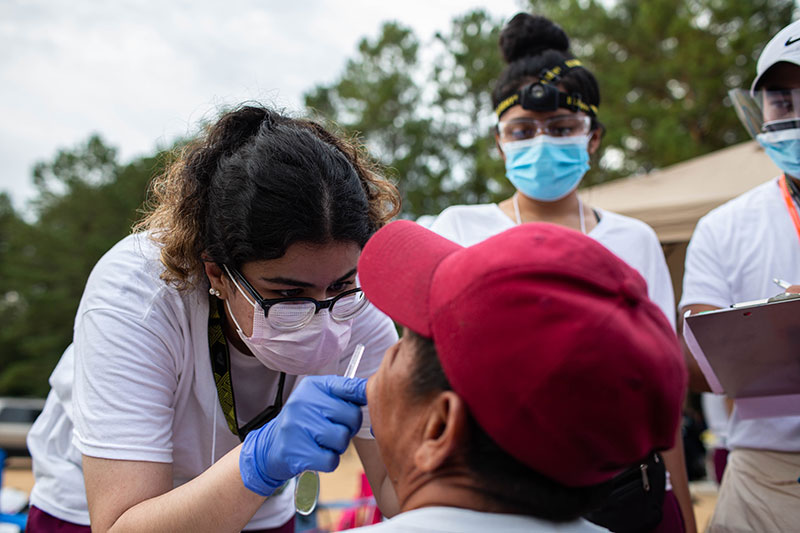

The volunteers quickly move the men and women through an assembly line of care—a basic checkup, physical therapy, oral health screening and massage.

In addition to basic health services, they also receive donated clothing and shoes that the students and volunteers collected prior to the trip and reap the benefits of an oral health exam station Clayton State University’s dental hygiene students manage.

Each patient receives an assessment and a bag with toothpaste, floss, toothbrush and other oral health items. This is the scene of the Farmworker Family Health Program (FWFHP), an annual service initiative where students, professors and other medical volunteers visit Colquitt County in southwest Georgia for two weeks each June to provide healthcare to migrant workers and their families who lack access to healthcare.

Crops are king in Georgia.

Peanuts, pecans and blueberries are some of highest produced crops in the state. And more than 22,000 jobs can be found in farming, fishing and forestry according to the Georgia Department of Economic Development.

To keep up with customer demand and get produce to the market, farmers rely on migrant workers, who often come from Mexico and Central America via the U.S. visa process, to plant and harvest crops. In return, the workers benefit from being able to earn wages to support their families.

The Farmworker Family Health Program steps in to take care of the medical needs of the workers and their families, which can reduce the burden of access to healthcare in the rural rich counties of south Georgia.

“These guys are working in the field 14 [to] 16 hours a day, so traditional clinic hours are not easy to get to. Access to care is the number one health problem in rural areas,” said Dr. Erin Ferranti, associate professor at the Neil Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing at Emory University and the director of FWFHP. “Bringing healthcare to where people are is a way to bridge that gap, open up care and refer them for anything beyond what we’re able to provide here out at night camp as well as the schools.”

The Farmworker Family Health Program was created 26 years ago after Georgia State University’s nursing program recognized the need to bring healthcare to the migrant worker population in south Georgia. The goal of the program was to merge healthcare with education. Migrant workers gain direct access to quality care at no cost while students earn valuable hands-on experience working with a vulnerable patient population.

Emory partners with the federally- funded Ellenton Health Clinic to address medical referrals migrant families receive during the screenings.

Eight years after the program formed, Dr. Judy Wold, a retired clinical nursing professor, took on the role of director-emeritus of FWFHP.

Wold expanded the program, developing partnerships with schools such as Emory University, Clayton State University and the University of Georgia to offer additional healthcare expertise to the migrant workers.

The collaboration between schools also means students learn from each other to understand how each specialty—be it dental hygiene, physical therapy or nursing—works together to improve a patient’s overall health.

“We have over 100 students that we bring every summer for two weeks and they’re able to work in the field [and] work interdisciplinary,” Ferranti said. “When they are working as a licensed professional, they have to work across disciplines and inter-professionally. Knowing the scope of the other disciplines opens their eyes to how they can collaborate more, advocate for their patient to seek care from the other disciplines and provide a full holistic provision of care. It’s a really neat thing. You can’t do this in an acute care setting.”

Ferranti took over the program from Wold, whom she calls her mentor, in 2019. She and co-director Laura Layne, deputy chief of nurse- quality improvement at the Georgia Department of Public Health, continue to build on Wold’s work by seeking greater financial support from donors as well as conducting a research study on heat illness among the migrant population.

Earlier that same day in June, the Clayton State students, along with nursing, physical therapy and pharmacy students from other Georgia schools, conducted well- child health visits for children at Len Lastinger Elementary School in nearby Tifton, Georgia.

The children, whose parents are migrant workers, each received an oral health screening, lessons on how to brush their teeth and sealants, thin protective coatings put on molars to prevent cavities.

The needs of the migrant workers and their families vary. The dental hygiene students usually find decay, abscesses and sensitivity in the teeth among the adults. A deep cleaning, or regular cleaning for a healthier mouth, also can be prescribed.

The children experience dental issues typical of most adolescents their age, like cavities. But dental education helps ease any fears or concerns that the migrant families may express to the students.

“I think patient education is really important because if they don’t [understand their health], then how will they take care of themselves,” said Ayumi Lashley, a senior dental hygiene major.

At times, the one-on-one interaction with the migrant families was quite eye-opening for the Clayton State students.

“Some of the children don’t even know how to brush; they just haven’t had that education,” said Jennifer Carmona. “As far as night camp, they are undertreated, and they just don’t have the support to go see a dentist.”

Conducting such a large number of dental checkups can be exhausting. Besides days that go on for 12 hours or more, the group faces extreme heat, language barriers and lack of computer access and traditional patient setups that are typically found in clinics and doctor’s offices.

“The more challenging thing for me was the weather,” Thanh Ngo quipped. “When I stepped out of the car, I was sweating.”

But seeing the bright smiles on the children’s faces and hearing from the migrant workers how grateful they are for the information and service that will help them maintain their health, makes the work worthwhile.

“They’re appreciative of [us] providing some type of care,” said Dr. Joanna Harris-Worelds, an assistant professor in Clayton State’s dental hygiene department. “Knowledge is often power. They’re happy to know that the problem they thought they had was not as pressing or concerning as maybe they once thought.”

To learn more about the Farmworker Family Health Program visit www.clayton.edu/laker-connection to see a video.

And to hear what one day is like for Clayton State dental hygiene students caring for the migrant families, listen to our podcast, the Laker Lounge, at the www.thelakerlounge.podbean.com.

By Kelly Petty

On the fifth floor of downtown’s hipster hangout, Ponce City Market, is Mailchimp, a leading email marketing platform known as much for its services as its mammalian mascot.

By Allison Salerno

At 22, Clayton Carte already is making a name for himself in local politics.

By Kelly Petty

When a committee of faculty and staff came together in 1994 to create a time capsule containing historical items from the school’s 25 years since its inception . . .

By Adina Solomon

When you move you consume oxygen. When you move fast, your heart rate and blood pressure rises. A metabolic cart can help improve the cardiovascular system of heart patients and athletes alike.