Share the Story on FacebookShare the Story on TwitterShare the Story via EmailShare the Story on LinkedIn

|

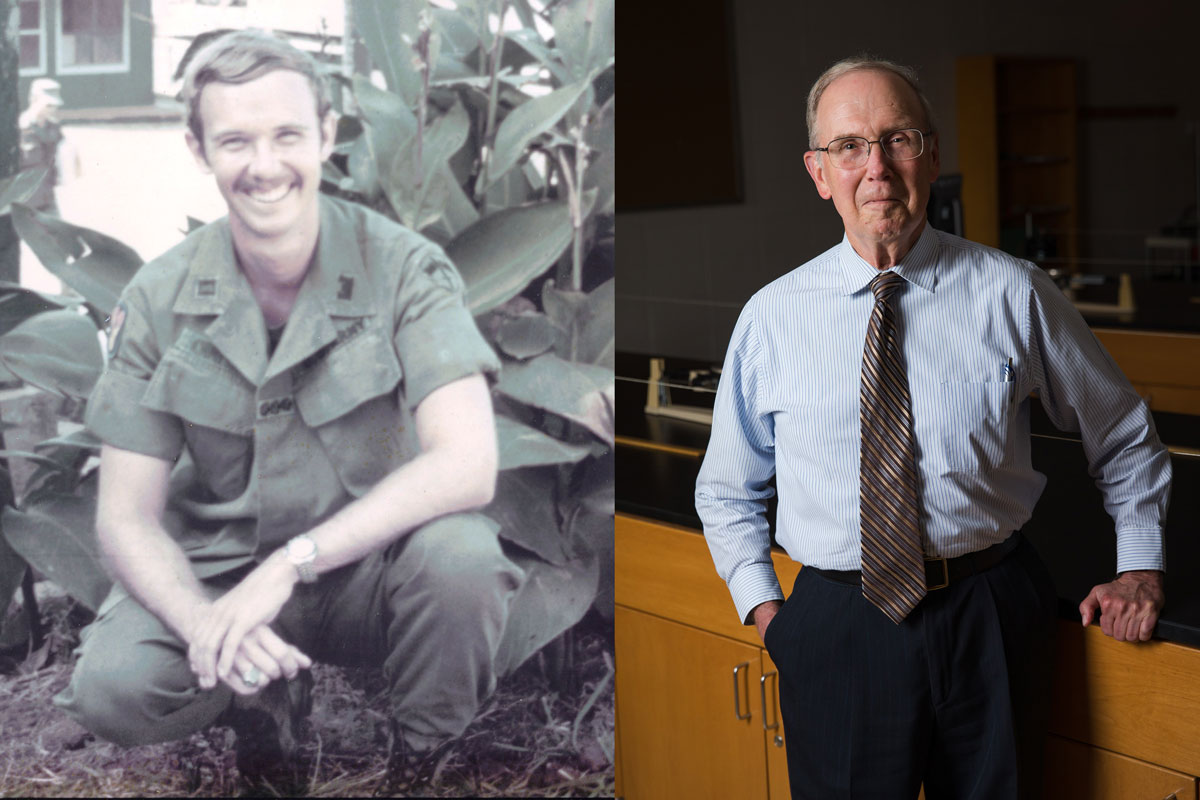

John Campbell - Faculty Profile

Step into Dr. John Campbell’s class, and you’ll quickly find out that the study of physics is less daunting than what it appears.

“Many people think physics is really, really hard stuff and that it is really difficult,” he says. “It isn’t. It’s clearly the simplest of all the sciences, by far the simplest.”

Whether it be the crack of a bat launching a baseball across a field or a collision between automobiles, physics, the study of the nature and properties of matter and energy, is all around us.

Campbell, a professor of physics and associate dean at Clayton State, has always been attracted to science and will tell you that, in some ways, physics found him.

Growing up as a military kid, Campbell’s family was stationed in Alabama when they decided to moved to Missouri right after he finished high school.

At the University of Missouri’s orientation to place students in different science disciplines, Campbell happened to sit in the area designated for physics students.

“I knew pretty much I wanted to be in math, or physics or chemistry,” Campbell remembers. “I said, ‘it’s a sign.’”

After college, Campbell embarked on his first career as a commissioned officer in the U.S. Army, where he served for 25 years.

His military training included basic airborne and jumpmaster courses to learn how to parachute out of military aircraft, as well as teach those skills to others.

Campbell did 10 jumps at various heights, sometimes as high as 1,200 feet.

“You’re more afraid of the jumpmaster than you are afraid of jumping out,” he says. “All you have to do is fall. The only tricky part is landing.”

He uses the parachute landing fall to explain how the maximum force of the landing can be reduced by applying one of the principles of physics, momentum, and its change in time.

“It is about what we can do to help students become better students,” he says.

Momentum—or to be more specific linear momentum—is the product of the mass of an object times its velocity. Mass, speed and direction are important to the concept.

“Parachutists are taught not to keep their legs rigid when they hit the ground, but to make contact with the ground along five consecutive points of their bodies so that the collision takes a longer time to occur. This reduces the maximum force they feel and reduces the probability that they get hurt,” Campbell explains.

As a longtime educator—he taught at West Point and Colorado State University before coming to Clayton State—and as one of the longest-serving tenured professors at the University, Campbell says the idea of momentum might be applied to academics.

Campbell says while momentum is a decidedly scientific term, it’s principles can be applied on campus over a period of time to support a strong academic environment that can empower students.

“It is about what we can do to help students become better students,” he says.

Read more stories from this issue